|

| Photo by Alison |

Remembering those who fought for New Zealand in the other localised wars across the globe, and those who grew not old.

1899-1902 Anglo-Boer War and following on from World War 2, 1948-1965

Our first international war was the Boer War of 1899-1902 in the Transvaal region of South Africa. Following the British annexation of Transvaal in October 1900, the conflict in South Africa entered a second phase: guerrilla war.

Rotorua men were recruited and of the men who went, only one did not come home. This soldier was Fred Wylie who was killed in action at Klippersfontein. Wylie was part of the 7th contingent, 8 Coy., he was a farmer who lived at Galatea. His father Mr Joseph Wylie was a teacher and JP.

Others who went from Rotorua are Henry Robert Seymour Corlett, his father was Mr. B.S. Corlett and George Steele, one of the brothers who owned the Sawmill on the corner of Tutanekai and Eruera Sts, was a Sergeant and was shipped out at the same time as Wylie and Corlett. New Zealand soldiers are recorded in Stowers ‘Rough Riders at War’, also recorded is the names of the Maori detachment, two Te Arawa men are named, E. Hikairo and A. Wiari. Stowers reports that some of the names in the list could be misspelt.

Maori were not welcomed by the British and were officially excluded from service in South Africa, however Premier Richard Seddon made a push for Maori participation:

although permission to form a Māori contingent was never received, the New Zealand authorities sometimes turned a blind eye to individual Māori who tried to enlist under English names. Most of those who succeeded were ‘half-castes,’ as those of mixed race were then generally known. Many were well-educated and fluent in spoken and written English. NZHistory.govt.nz.

Stowers also mentions the Māori nurses and orderlies who served during 1900, one such orderly was Petera Waaka (Tuhourangi). No further information is mentioned here.

The Wylie Memorial was commissioned and Mr Parkinson of Auckland was appointed, completing the statue by January of 1904, it was unveiled c.19 January 1904. The statue comprised a water fountain at its base and above a representation of the fallen soldier. Other memorials like this one were also erected elsewhere in NZ.

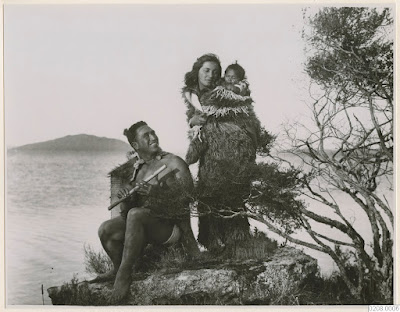

Price, William Archer, 1866-1948: Collection of post card negatives. Ref: 1/2-001505-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

natlib.govt.nz/records/23080236

After World War Two...

JayForce 1946-1948

Outside of the well documented WW1 and WW2, JayForce was

formed and served in Japan, as the New Zealand contingent of the British Commonwealth

Occupation Force.

Many Rotorua men were sent overseas for World War 2 and some

stayed on moving to JayForce and serving there for the following reason:

The Commonwealth troops were to oversee Japanese demilitarisation and demobilisation. Jayforce was initially deployed in Yamaguchi prefecture on the southern tip of the main island of Honshu, and on nearby Eta Jima Island. This was a relatively poor rural region with a population of 1.4 million – not much less than New Zealand’s total population at the time. The New Zealanders’ first task was to search for military equipment. Little was found, as Yamaguchi had not had a major military presence during the war. Jayforce also assisted with the repatriation of Japanese who were coming home and Koreans who were being returned to their own country… An April 1948 decision to withdraw Jayforce from Japan was implemented by early 1949. (NZHistory.govt.nz)

Approximately 45 Rotorua men were part of the BCOF you can find their names on the Auckland War Memorial Museum Online

Cenotaph

Recognition for Jayforce, was the New Zealand Service

Medal 1946-1949, not issued until 1995.

|

| Photo by Alison, courtesy of Kete Rotorua |

KayForce 1950-1953

Prior to New Zealand’s armed forces became involved, it was reported in February 1949 that ‘South Korea has been invaded by Soviet trained troops with Russian rifles, machine guns, mortars and field artillery’ (Ashburton Guardian, 1949) Officially the war began 25 June 1950. In July of 1950, Koreans living in Japan were called upon to “rise and sabotage the war effort of the United States” (Ashburton Guardian, 1950).

New Zealand’s 1056-man Kayforce arrived at Pusan, South Korea, on New Year’s Eve 1950. It was part of the United Nations’ ‘police action’ to repel North Korea’s invasion of its southern neighbour. The New Zealanders joined the 27th British Commonwealth Infantry Brigade and saw action for the first time in late January 1951. Thereafter they took part in the operations in which the UN forces fought their way back to and across the 38th Parallel, recapturing Seoul in the process.

Of those enlisted were 292 were from Rotorua, listed in the Rotorua Morning Post from 28th July 1950 to 4th August 1950, a further enlistment occurred in June 1951 and January 1953.

In November of 1951 an article printed in the Press (Christchurch) reports that the North Korean Foreign Minister made a four-point proposal to the United States to end the Korean War. However it was not until 1953 that armistice was finally reached. The Russian Prime Minister immediately offered congratulations to Kim Il Sung and also offered assistance to help ‘rehabilitate Korea’.

It was an uneasy truce it seems because reports came from Taipei that the Republic of Korea would take military action if a general war flares up in the Formosa Strait, since the Korean Communists had violated the truce agreement. (Press, 1955)

However New Zealand had recalled Kayforce and in the Rotorua Post of 18 June 1957, this small article appeared on the front page:

K-Force Men to return, only about

70 men will return in August. The troops

go by sea to Hong Kong and will fly home in an air force aircraft, No.41

Squadron via Singapore, Darwin and Amberley, finally arriving at Whenuapai

August 10th & 11th.

Rotorua Post (1957, June 18).

|

| Photo by Alison, courtesy of Kete Rotorua |

Malayan Emergency 1952-1966

Three British planters in northern Malaya in

1948 were murdered. This brought on

hostilities in Malaya dubbed the Malayan Emergency, once more called for

international help. A guerrilla campaign

was mounted by the military arm of the Malayan Communist Party against British

forces. New Zealand got involved in 1949 when several

army officers served while on secondment with British units.

Since the situation in Malaya was still ongoing, NZ called

for SAS volunteers. Four Rotorua men enlisted and undertook training, and embarked

among the 190 strong contingent. They were Clive P. Ngatai, Buck H. Rogers and

Mathew Tamehana and Sonny Osbourne. Rotorua

Post. (1955. October 25).

Later once the need for soldiers increased the Rotorua Post

reported:

‘Recruiting will start tomorrow for Malayan

Battalion’

The Minister of Defence, Mr

Macdonald said recruiting for an infantry battalion would start on the 19th

of June at all army offices. The Army sub-area office in Rotorua is in the

Mokoia Buildings at the corner of Hinemoa and Tutanekai Streets.

The article goes on to say

The force will be known as the New Zealand Army Force,

Far East Land Forces. The force is to be drawn mainly from new

enlistments…volunteers will have the chance of the normal five years regular

engagement of three years…applications will be accepted from men between the

ages of 21 and 35, with preference given to single men under 30. 20 year olds

would be accepted providing they had their parents’ consent’’ (Rotorua Post,

1957)

In August of 1957 a

photograph was published of all the Rotorua men who were leaving by bus for

Papakura that day, later on page 6 the men were named. Those men were D. Trueman, K. McGregor, G.

Midwood, N. R. Mackay, V. Ratana, F. Eruini, D. Rogers, F. Clarke, R, Te Kiri,

A. Williams, M. Curtis, D. Unsworth and P. Morehu’

Others in the photograph could be from Atiamuri:

B. Slade, S.

Kopa, R. Cassidy and G. Cassidy

Taupo: G.H. Grant. Wairakei: G. Muller, Murupara: M. Tipoki,

Mangakino: B. Middleton and R. Lloyd (Rotorua Post, 1957)

Recruits were given basic

training at Waiouru, Burnham and Papakura, the central North Island recruits

were sent to Papakura before being flown to Malaya from Auckland.

It was to turn into a long

drawn out ‘confrontation’ and in October of 1959, the Christchurch Press

reported that ‘As the Malayan emergency drags through its twelfth year, members

of the RNZAF stationed in Singapore are still helping the Commonwealth effort

to eliminate the remaining terrorists in the Malayan jungle’. The RNZAF continued to deliver aid to the

forces on the ground throughout the final drawn out year.

The Rotorua men all returned home, some in time for

Christmas in December of 1959 the rest by early 1960. One Rotorua soldier

returned with an English wife, she had been a dentist at the Kuala Lumpur

military hospital and six other soldiers married Malayan girls. (Rotorua Post,

1959)

Those who returned had harrowing stories and some that have

never been told.

Other New Zealand peacekeeping forces continued to be posted

to Malaya between the years 1960-1964.

Indonesia / Borneo c.1962-1966

Fighting over territory in Borneo had

long been a problem for all involved, namely Britain, The Netherlands, Japan,

Philippines, Indonesia and Malaysia and in the middle of it all the Dayaks who

are the indigenous people.

Border skirmishes continued between

Malaya and Indonesia and North Borneo, Sarawak and Singapore and the Indonesians carried out

armed incursions and acts of subversion and sabotage, including bombings, to

destabilise the federation. Singapore experienced a series of bombing

incidents, which killed seven people and injured 50 others. (nlb.gov.sg)

British and Commonwealth forces including Australians

supported Malaysia. At stake was the future of the former British possessions,

Sabah and Sarawak, which bordered Indonesia's provinces on Borneo. (dva.gov.au)

This new dispute was named a ‘confrontation’

beginning in 1963 it finally ceased when on 11 August 1966 when a peace treaty

was signed in Bangkok. New Zealand had

not sent soldiers until 1 February 1965, after a request from the Malaysians. A

limited SAS detachment and two former Royal Navy minesweepers, renamed HMNZS Hickleton and Santon were to join the frigate HMNZS Taranaki patrolling in the Malacca Strait.

Troops and air force pilots were deployed, approximately

28 Rotorua men served in Borneo.

New Zealand’s involvement in this complex area of

the world was ended after the treaty was signed, the news articles of the day

mention that they should be home by November of 1966.

|

| Photo by Alison, courtesy of Kete Rotorua |

Vietnam War 1961-1975

New Zealand’s involvement began in April 1962 when capital and civil technical assistance and in 1963 a civilian surgical team arrived in Vietnam and NZ’s contribution continued in providing aid.

The first New Zealand troops into action were the gunners of 161 Battery, Royal New Zealand Artillery. On 16 July 1965, they fired their first shells near Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City). New Zealand came under renewed pressure from US President Johnson to expand its commitment in Vietnam. In 1967, NZ sent two infantry companies – V and W – from the 1st Battalion, Royal New Zealand Infantry Regiment in Malaysia, along with a tri-service medical team – 1st New Zealand Services Medical Team. A Special Air Service (SAS) troop arrived the following year.

NZ forces were involved in artillery offensives, cordon and search patrols, intelligence gathering and reconnaissance missions around Phuoc Tuy province. New Zealand gunners were one of three field artillery batteries comprising part of the 1st Australian Task Force (1ATF). Kiwi infantrymen made up two of the Anzac Battalion’s five company-sized units. A 26-man New Zealand Special Air Service (NZSAS) troop completed the Australian SAS squadron at Nui Dat. (nzhistory.govt.nz)

'Vietnam War map', URL: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/photo/vietnam-war-map, (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 15-Sep-2014

Here is some local information regarding men who enlisted in Rotorua:

Gunner Alan Scott only Rotorua man to join V-Force (Rotorua Daily Post, 1965)

Following this in 1967 when New Zealand agreed to send more troops many more young men from this district enlisted.

Enlisting at the Rotorua sub-office was the only option for men from the Bay of Plenty towns like Edgecumbe, Murupara and just to the south from Taupo and Turangi, Mangakino etc. also it is documented that the Infantry battalion was replaced from Malaysia after serving 1 year there.

New Zealand's commitment peaked at just over 500 troops in 1968. The last Kiwis left South Vietnam in December 1972. The last American troops left the following year. By the time the war was finally over, at the fall of Saigon in April 1975, more than three and a half million people had died. (North & South. May 2018, Issue 386, p67-81)

|

Polynesian Protest 1972, note two Bay of Plenty identities Tame

Iti and John Ohia,

Photograph courtesy of John Miller |

How this controversial war affected Rotorua residents is covered in the Rotorua Daily Post from 1965-1972, also mentioned are the names of the young men who enlisted and came home changed forever and those who did not return.

See also https://vietnamwar.govt.nz/

Rotorua men and women have been involved in many other horrific wars since this time and continue to serve our country wherever they are needed.

References:

1. Stowers,

R. (2002). Rough riders at war. R.

Stowers.

Press. (1949, February

4). South Korea invaded: 1000

Soviet-trained troops. Press.

Press. (1950, June

26). State of war in Korea: northern

armies invade south. Press.

Rotorua

Post. (1955, May 21). M-force men on final leave. Rotorua

Post.

Rotorua

Post. (1957, June 18). Recruiting will

start tomorrow for Malaya Battalion. Rotorua Post.

Rotorua

Post. (1957, June 18). K-Force men to be

home in August. Rotorua Post.

Rotorua

Post. (1957, June 19). FN rifle will be

weapon of new Malaya force. Rotorua Post.

Rotorua

Post. (1957, August 1). They’re in the

army now. Rotorua Post.

Rotorua

Post. (1957, August 1). Malaya Force men

leave for Papakura. Rotorua Post.

Rotorua

Post. (1959, Dec 17). Rotorua men would

be happy to go back to Malaya. Rotorua Post.

Rotorua

Post. (1965, June 6). N.Z. Battery gets

‘go ahead’. Rotorua Post.

Rotorua

Post. (1969, May 26). [Untitled

photograph]. Rotorua Post.

Rotorua

Post. (1970, June 20). Rotorua soldier

suffers wounds. Rotorua Post.

Rotorua

Post. (1970, November 2). Rotorua soldier

injured. Rotorua Post.

Te

Pae Wānanga, Research and Publishing Team. (2021). Main body of Jayforce lands in Japan. Ministry for Culture and

Heritage. https://nzhistory.govt.nz/jayforce-arrives-in-japan

Te

Pae Wānanga, Research and Publishing Team. (2018) South African War, 1899-1902. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. https://nzhistory.govt.nz/war/south-african-boer-war/introduction

Te

Pae Wānanga, Research and Publishing Team. (2020). New Zealand in the Korean War. Ministry for Culture and Heritage.

https://nzhistory.govt.nz/war/korean-war

Te Pae

Wānanga, Research and Publishing Team. (2021). NZ and the Malayan Emergency.

Ministry for Culture and Heritage. https://nzhistory.govt.nz/war/the-malayan-emergency

Rotorua Post.

(1959, Dec 17). Rotorua men would be happy

to be back in Malaya. Rotorua Post.

Te Pae

Wānanga, Research and Publishing Team. (2021). NZ and Confrontation in Borneo. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. https://nzhistory.govt.nz/war/confrontation-in-borneo

HistorySG. (2014). Konfrontasi (Confrontation) ends - Singapore

History. nlb.gov.sg

DVA (Department of Veterans'

Affairs) (2021), The Indonesian

Confrontation 1962 to 1966. https://anzacportal.dva.gov.au/wars-and-missions/indonesian-confrontation-1962-1966

Te Pae Wānanga, Research and

Publishing Team. Vietnam War. Ministry

for Culture and Heritage. https://nzhistory.govt.nz/war/vietnam-war.

Ministry for

Culture and Heritage. On operations |

VietnamWar.govt.nz, New Zealand and the Vietnam War

Stanley, B. (2018). Brothers in

arms. North & South.